This is part one of a double bill on supervision and diversity, by Dr Jessica Gagnon (@Jess_Gagnon) an educational sociologist, focused on inequalities in higher education. She has worked in higher education in the US and UK for more than 20 years. Jessica is a first-generation student from an American working-class, single mother family. She currently serves as co-chair for the Gender and Education Association, an international, intersectional feminist academic charity founded in 1997, focused on achieving gender equality within and through education. The second part to this post shares a wealth of ideas for supervisor practice.

Content note: This blog post discusses and references systemic inequalities, bullying, harassment, gender-based violence.

Our universities are very good at talking about diversity, but good intentions are not good enough when systemic inequalities still persist. What does that mean for those of us who serve as supervisors for doctoral students?

Change for good

Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) should be at the heart of all of the work that we do within academia.

I don’t just mean the ways that our institutions showcase their adherence to laws related to protected characteristics, like the Equality Act, through annual reports. No gold stars for basic legal compliance.

I don’t just mean basic recognition of diversity, where institutions do the bare minimum of raising a rainbow flag during LGBTQIA+ history month or recognising Black History Month with a Tweet. No pats on the back for basic recognition.

I also don’t just mean empty commitment statements that our universities often make. How many of our universities have hiring, promotion, or pay gaps for staff and withdrawal or attainment gaps for students based on race/ethnicity, gender, disability, sexual identity, or caring responsibilities?

How many of those same universities publish phrases like ‘We value diversity’ or ‘We’re committed to equality’? Those phrases are meaningless unless evidenced by transparent data, fully embedded inclusive practices, and robust accountability mechanisms so that we can be sure that our institutions live up to the commitments that they have made.

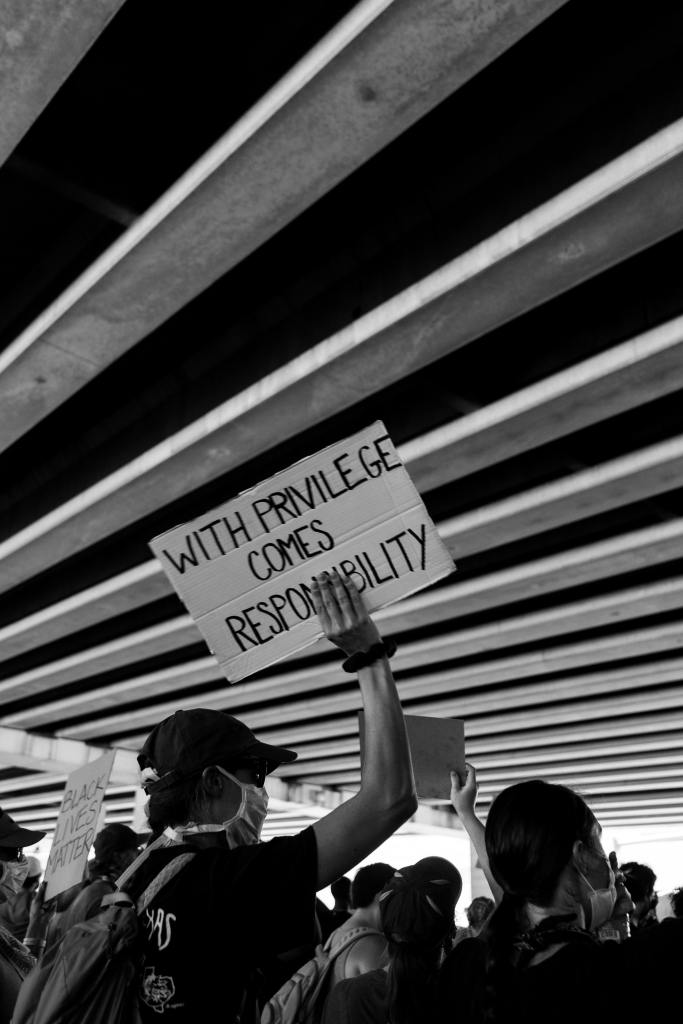

A reckoning of justice has long been coming for the higher education sector, with more and more pressure for change applied by groups like TIGER in STEMM and the 1752 Group, movements like Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, and #MeToo, and campaigns like Everyone’s Invited and Students Not Suspects to try to hold academia accountable.

There is some (slow) progress towards transparency and accountability when it comes to the work necessary to fully embed JEDI into academia. For example, AdvanceHE/the Higher Education Academy requires that those applying for the different levels of Fellowship to account for EDI (Equality, Diversity, Inclusion) in their pedagogical practices, as evidenced in Professional Values 1 and 2 of the Professional Standards Framework. Use pages 14-21 of this issue to consider your own classroom practices.

It’s also becoming more commonplace for governments and research funders to require Equality Impact Assessments (EIA) to be completed for new funding calls, policies, events, and initiatives.

JEDI in doctoral supervision: our great responsibility

What I do mean when I talk about JEDI in academia is that the work should begin with a reframing of the narrative.

We should not do JEDI work just because it is the right, moral thing to do (though it is). JEDI should be at the heart of all of the work that we do because inclusion is essential.

As multiple studies have shown: more inclusive working environments lead to better innovation, more resilient organisations, and greater economic growth. Inclusive working cultures can lead to higher productivity of underrepresented staff. These studies provide evidence that help us to state the obvious: students and staff who are fully included, feel like they belong, believe that their voices are heard, know that their contributions are valued, are likely to be more innovative and productive.

So, JEDI is not something ‘nice’ our universities do as some sort of ‘favour’ for underrepresented or marginalised students or staff. Our institutions should be fully embedding JEDI into policies and practices because the consequences for not doing so can be (and should be) detrimental, including the loss of the contributions that could have been made by marginalised students and staff, reputational damage for headlines like this one and this one, and also financial losses from legal settlements like this one and this one.

As supervisors, given the inequalities in withdrawal and in PhD completion rates among underrepresented doctoral students, we should be asking ourselves:

In what ways does society lose out on the contributions those students could have made to knowledge, to innovation, to solutions for local, national, and global challenges, to creating a better world?

A review of nearly two decades of literature on the doctoral experience found that the supervisory relationship is the “most widely researched factor, and considered to be the most influential in the doctoral experience”. To paraphrase a saying that’s been around for hundreds of years but was made more famous in the last century by Stan Lee: With great power and privilege comes great responsibility. Our great responsibility as supervisors is to ensure that we are providing the guidance and support our supervisees need to thrive (as much as possible) within a system that has been built to exclude many of them. This includes supporting our supervisees to navigate through a deeply unequal system whilst simultaneously actively working to dismantle those systemic inequalities.

We start here by understanding the extent of the evidenced inequalities in the doctoral experience.

As with all areas of society, structural inequalities persist in higher education, including in the doctoral experience. Here I include just some of the data related to inequalities and challenges PhD students face.

- More than one in five PhD students indicated that they have experienced discrimination or harassment (source).

- One in four PhD students indicated that they have been bullied (source).

- More than one in three PhD students have sought help for anxiety or depression caused by their PhD (source). In fact, only 14% of postgraduate research students reported having low anxiety, compared with 41% of the general population (source).

- More than three out of four PhD students indicated that they are working 41 or more hours a week on their PhD (source). We know that overwork and burnout have become commonplace in academia, but not everyone can (for example, PhD students with caring responsibilities or disabled* PhD students) and no one should have to work hours that are not conducive to good health and wellbeing.

- Nearly one in four students of colour reported experiencing racial harassment in UK universities (source). White applicants are more likely to be offered a PhD place in the UK (source). Concern has been raised that the process for selecting UKRI funded PhD students disadvantages/discriminates against applicants from underrepresented backgrounds (including People of Colour**, disabled applicants, and applicants from low socio-economic backgrounds) (source).

- Men are overrepresented in elite PhD programmes in the US (source). Some studies show that women are more likely to withdraw from their doctoral studies and take longer to complete than men (source). The gender gap in completion rates is worse in programmes where a woman is the only or one of only a few women in a PhD cohort (source). In some subjects, the completion rates for women are higher than for men (source).

- Doctoral students engaged in teaching are subjected to biased student evaluations (source).

- Nearly one in four PhD students would change their supervisor if they could go back and start again (source).

What can we do to take action?

As supervisors, our time is limited and we cannot solve systemic inequalities single-handedly. We are working within the same unequal system that we are trying to change and we are not responsible for solving the whole problem. However, there are things we can do to make a difference. Tomorrow’s post, part two of this double bill, will discuss those in detail, once you have had chance to digest the issues of inequality our junior colleagues face.

Your thoughts and experiences are welcome in the comments.

Footnotes

*I use disabled people rather than people with disabilities in recognition of the social model of disability. Read ‘Why we are disabled people, not people with disabilities’. Watch Scope’s video ‘What is the social model of disability?’

**I am using PoC (People of Colour), though I also recognise the criticisms of umbrella terms for underrepresented and marginalised groups as they do not fully reflect the diversity of possible identities. People of Colour (PoC) was first in print in the 1700s though the phrase has been in more popular use over the last few decades. Watch Loretta Ross discussing the origins of the phrase Women of Colour.

Reblogged this on Digital learning PD Dr Ann Lawless and commented:

Justice Equity Diversity Inclusion (JEDI) in HE

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Auditorium and commented:

How to take a justice, equality, diversity and inclusion approach to doctoral supervision.

LikeLike